Paul Tazewell sits down with ET to discuss the process of bringing Harriet Tubman to life.

Costume designer Paul Tazewell won a Tony Award for dressing Alexander Hamilton and his fellow Founding Fathers in their 18th-century garbs for Lin-Manuel Miranda's Hamilton. His follow-up is a more modern project, although only by 50-or-so years: Harriet, about history's preeminent conductor of the Underground Railroad.

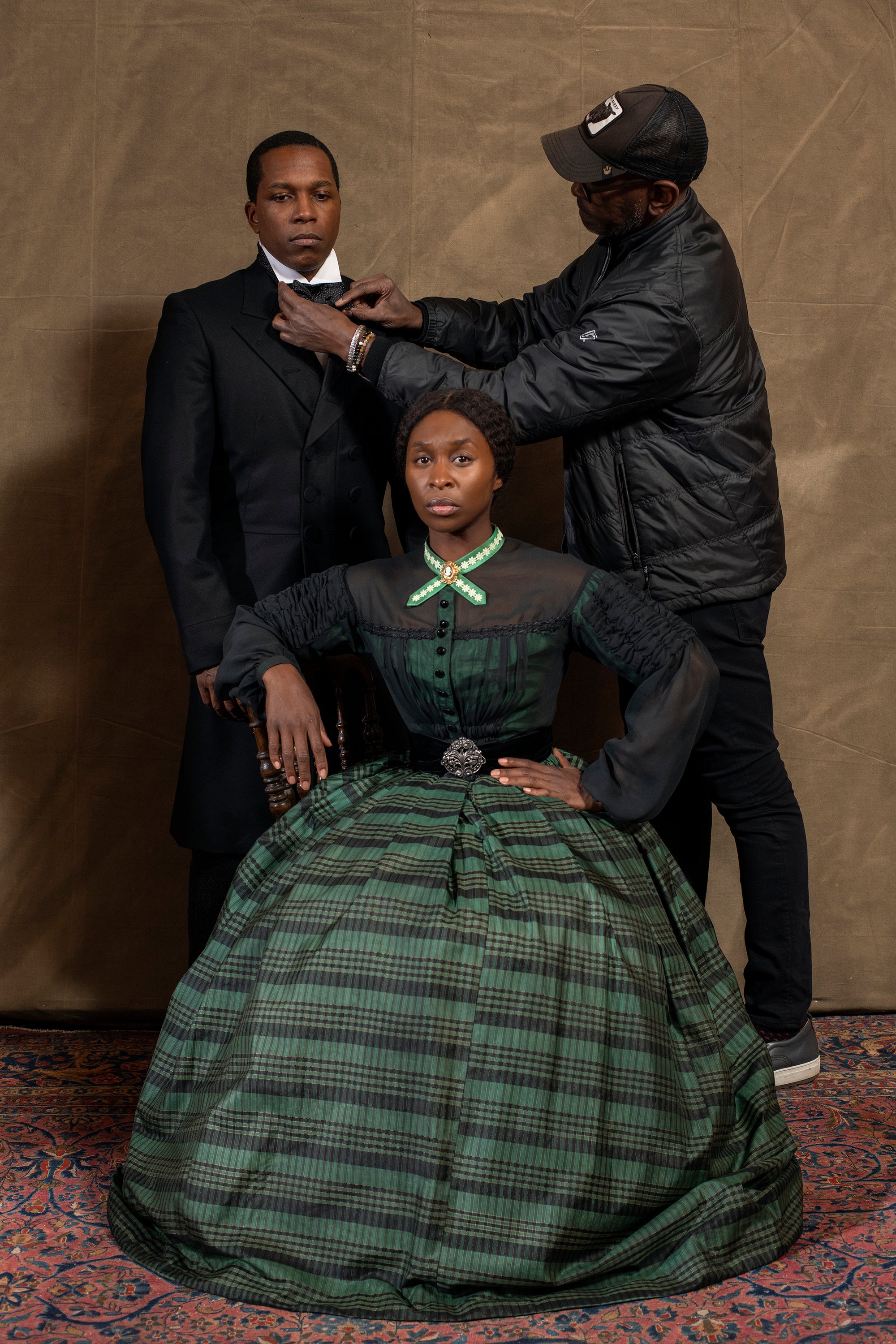

Director Kasi Lemmons' biopic tracks Harriet Tubman's journey to freedom, from slave to a master spy, activist and abolitionist. As played by Cynthia Erivo, Tubman's transformation is reflected at every turn in Tazewell's costumes, just as the clothing worn by Erivo and her co-stars (including Janelle Monáe and Leslie Odom Jr.) are meant to reveal shades of the time they lived in.

"Someone might not really realize because there was so much focus on, 'Well, most of black America were slaves and then all of white America were the rich people," Tazewell explained. "No. It's much more complicated than that and beautiful. With clothing, what has always been front and center is the use of clothing for self-confidence or self-esteem and showing this really strong sense of humanity. You see it all the way through the periods. With the means that black people had -- even on the plantation -- there needed to be a sense of using clothing as a way to hold onto your dignity."

With Harriet now in theaters, Tazewell sat down with ET to discuss the process of bringing Harriet Tubman to life onscreen.

We've seen Harriet Tubman onscreen before, but never to this extent. When you set out at the start to create what will be a defining representation of Harriet Tubman for many people, what were some of those things you wanted to say about her through your costume design?

Foremost in my thinking -- and it relates to where Kasi Lemmons, the director, was in interpreting our story -- I just wanted for our new vision of Harriet to be noticed, to not be skipped over. Most of what we have as representation are photographs of her when she was older -- older than the time that we actually see her within the story of the film -- and inspired by a newly found portrait, we see her as a young woman and a woman that has a sense of style. And there's a softness about her that you don't actually see in some of the other photographs. And I think that it was just adding to [and] broadening the image of this icon.

Your big gig before this was Hamilton. They're obviously set during different time periods, but is there anything that you're able to bring over from that as you start on this?

I think that the experience from production to production, whether it's a theater production or a film, one informs the other. I'm always learning from working on it and immersing myself in whatever the period is. But it's not as direct or obvious. As you said, it's a completely different period. But what I take from all of my work and understanding period detail and understanding how I see research and interpreting that research and how I'm able to use that to interpret character and support the story, that's all connected. My ability to do Harriet is informed by everything that came before it. So yes and no. I don't know that it's something that you could take a look at Harriet and say, "Oh, well this kind of feels like [Hamilton]."

Beyond looking at the portraits of Harriet that we do have, where else did your research for this take you?

Largely, it was the daguerreotypes, and there are a lot of them -- in archives all over, within the Smithsonian, through the Schomburg Library, a huge amount is online. They had just started to use photography to document overall life and with that was life on the plantation and slaves and also free people of color, as well. And with those daguerreotypes of people that we don't know, there were all the daguerreotypes of people like Frederick Douglass or John Brown and other senators that actually existed. So there is, indeed, a lot that is representative of what people actually wore in that period. I collected as much as I could find and just drank it all up and then started to make specific choices to support the characters within the film. You're always faced with the actor that's playing the role and then who the real person was and how you bring those two together so that it's all believable.

What was the process of bringing together what we've seen of Harriet with Cynthia, then?

Cynthia is her own fashion icon. Every time that we see her outside of this role, she's hugely glamorous and really embraces that. When she's tasked with a role, she immerses herself in interpreting that role and she's true to that, but knowing who she is and her love of clothing, I knew that she would be able to wear this period clothing in the right way, in a very elegant way. But also she would buy into everything that it was going to require. I mean, she was trussed up in a corset and beladen with petticoats all the way through, even when she was trekking into and across a river and running through forests and through plantation fields. It was physically pretty strenuous. But we start with her as a slave and hugely oppressed and abused and we need to see her arc as she becomes a free person, starts to transform and take hold of her power as this superhero.

When you were designing these costumes, did you make allotments knowing the physicality that will be required of Cynthia? Or keep it true to the time and let that inform her performance in how difficult it actually would have been?

One of the things that was so beautiful in Cynthia is that there was a stunt double for her, and she would always put up a fight. She really always wanted to do her own stunts. So that informed everything. She wanted to feel what it really felt like or as close as possible. With Hamilton, I've got a cast full of women in corsets that have elastic sides so that they can move and function the way that they need to for that choreography. For Cynthia, she wasn't about that. She wanted for it to be exactly as it might've been, built exactly as it might've been so that she could really use that for her character work.

When you sign onto a period piece, how much do you personally hope to keep your designs true to what it would have been then and how much do you allow yourself to consider the advancements that have been made in the time since?

You make a judgment, as far as how does it serve the story and how it's being presented. Hamilton, because it's a musical, because it has to function in a very specific way with the choreography and you've got women that are playing men at times and then they go back to playing women, that has very specific requirements. With Harriet, we were in real spaces. We were in period rooms that were fully fleshed out. She was running through the field with her passengers and that was a real forest. So you think about function: "What does it take for me, as Harriet, to run through the forest and carry all these passengers and be ready for any natural elements that she might encounter?"

Although there was poetic license that I took as we transitioned into what I call her "power look," in the red coat and red dress. Some could say that was a theatrical take, but I think there were cues that I laid into those looks that were much more based in reality, based in real period, with the way she put together her bandit look when she's got a skirt and bodice on with a man's coat and a red headscarf and broad-brimmed hat. She's creating who she is as a person, and one of the things that was really exciting to design was how she became a master of disguise and what kind of disguises she decided to use. So she became a Blackjack, which is an African American sailor surrounded by black men sailors. She dressed herself that way. It was taking on these different disguises so that she could ride under the radar of the slave catchers and the police force, etcetera.

Considering the number of looks she has in the movie and variants and duplicates that had to be made because of the wear and tear they go through, do you know how many costumes you made for Cynthia, in total?

Oh gosh. [Laughs] I don't remember! I know that for the first slave, we had to make 12, because we needed to show the wear and tear of that costume. Each of them was distressed to a different level. And then there were clothes that were built for the stunts to match. There were fewer of the green dress that she is given by Marie Buchanon, the character that Janelle Monáe plays. Upwards of six to eight because we see how it starts to deteriorate [on] her travel back. Look-wise, we were probably upwards of 12 different looks.

You mentioned a number of the looks she wears over the course of the movie. Do you have a piece or a look or design element you've incorporated that you are particularly proud of?

I'm proud of how all of it works together. I think where it all came together was actually the first scene that we shot, was her bandit look where it shows how resourceful Harriet was as we were interpreting her, where she's working with a marriage of both female clothes and male clothes to put together a look that's really strong and powerful.

RELATED CONTENT: